Chesterton's Fence, Bayes' theorem, and the decay of tradition

I've been aware of the principle of Chesterton's Fence for quite some time, but I came to appreciate it in a deeper way after learning more about Bayes' theorem and its applications. Bayesian statistics have also helped me better understand another passage of Chesterton's, in defense of tradition. Below is a little reflection on what I have learned.

Encountering Chesterton

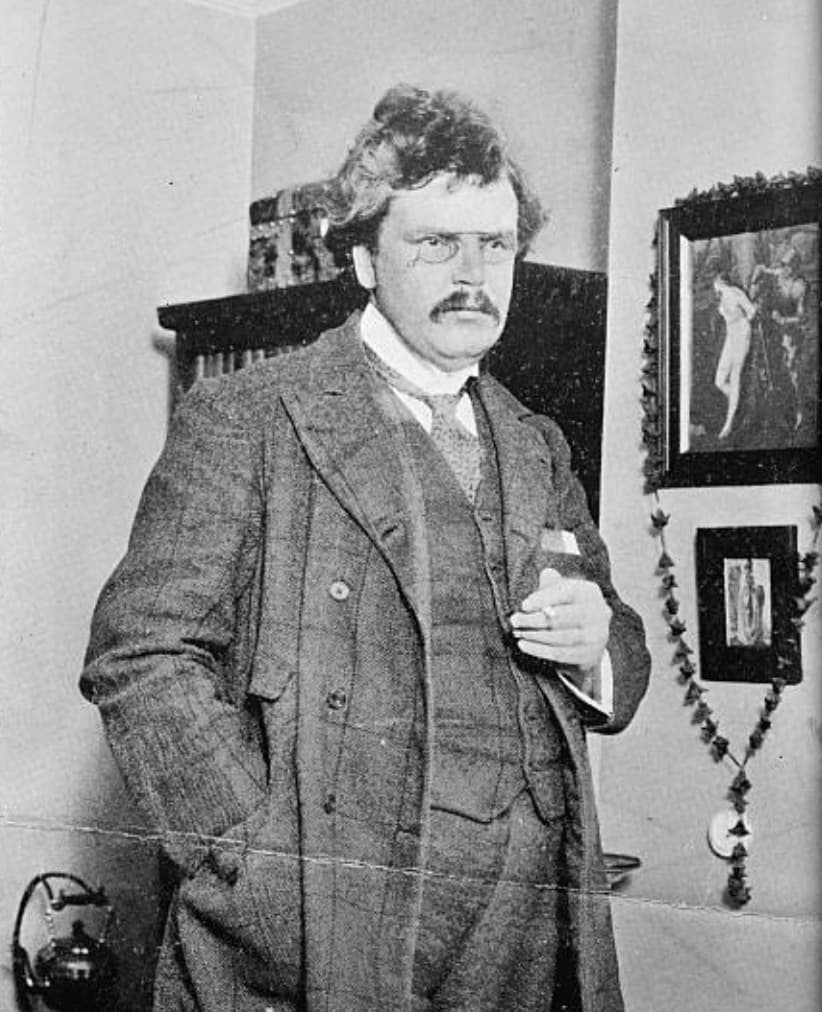

I first learned about the prolific early 20th century writer G.K. Chesterton a few years after I earned a degree in English, and I remain irked, some 20 years later, that none of the professors in my major saw fit to expose me to his body of work.

For someone with such an outsized profile — the New York Times described him in a rare front-page obituary as "for more than a generation the most exuberant personality in English literature" — it is puzzling that his name and works are recognized only in niche circles now.

Chesterton was a political essayist who inspired Mahatma Gandhi to lead a movement for Indian independence and Michael Collins to lead an Irish revolution. He was also a mystery writer who strongly influenced Agatha Christie, J.R.R. Tolkien, Alfred Hitchcock, and Orson Wells. He was a writer of apologetics, whose writings contributed to C.S. Lewis' conversion to Christianity. And he, along with Hillair Belloc, was a champion of a "third way" economic system called distributism, whose ripples we still see today in the form of worker cooperatives and credit unions.

On the fence

In software engineering circles, he is best known for a principle called Chesterton's Fence, which he describes in his 1929 book "The Thing":

There exists in such a case a certain institution or law; let us say, for the sake of simplicity, a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, "I don't see the use of this; let us clear it away." To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: "If you don't see the use of it, I certainly won't let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it."

The way I read this, Chesterton is cautioning against rash decisions and making an appeal for humility on the part of reformers. Things that at first glance seem nonsensical may, upon further reflection, have an important purpose. But we need to be willing to do that reflecting, rather than being dismissive of the possibility that there may be some explanation that didn't immediately occur to us.

When I've read discussions about Chesterton's Fence among software engineers, I've been struck by how controversial it is. To me, it seems like common sense — yet, as Chesterton himself observed, "The surprising thing about common sense is how uncommon it has become."

The democracy of the dead

Before I delve into how Bayes' theorem has helped me interpret Chesterton's Fence, I'd like to introduce another quote by Chesterton, this one about the value of tradition:

Tradition means giving a vote to the most obscure of all classes, our ancestors. It is the democracy of the dead. Tradition refuses to submit to the small and arrogant oligarchy of those who merely happen to be walking about. All democrats object to men being disqualified by the accident of birth; tradition objects to their being disqualified by the accident of death. Democracy tells us not to neglect a good man’s opinion, even if he is our groom; tradition asks us not to neglect a good man’s opinion, even if he is our father.

That quote comes from Chesterton's book "Orthodoxy," published in 1908.

If you can figure out what this quote might have in common with the previous quote about the fence, you get extra credit! If not, read on.

Bayes' theorem

Thomas Bayes was an 18th-century clergyman and mathematician who formulated a novel way to compute probabilities. But he never published it, and it was by mere chance that his friend Richard Price discovered it among his papers after his death and recognized its significance. Price edited the writings and published them, and now, some 260 years later, Bayes' theorem is a cornerstone of statistics.

One of the interesting things about Bayesian inference is the concept of updating one's prior knowledge with new data. The new data doesn't invalidate the prior knowledge; rather, both the old and new evidence are evaluated together.

For instance, if I'm trying to determine whether I'm flipping a fair coin, I might start out with the belief that there's a 99% chance that it's fair, based on how infrequently I have encountered biased coins in the past. If the first two flips both land on heads, I am not going to immediately jump to the conclusion that it is biased, not only because there's a 25% chance of that outcome even with a fair coin, but also because of the weight I'm giving to my prior evidence. Of course, if I flip the coin 10 or 20 times, and it lands on heads each time, the new data begins to outweigh the prior evidence, and it would be reasonable for me to adjust my beliefs accordingly.

Decay of priors

A coin's fairness or bias will remain more or less constant over time. If a coin has yielded 50% heads and 50% tails over the course of 10,000 flips, we can be fairly sure that it will not suddenly begin showing a strong bias toward heads.

That is not true in all domains. When it comes to weather forecasting, for instance, we might determine that it's reasonable to ascribe more weight to the prior evidence we collected last week than to the prior evidence we collected this time last year.

Thus, many practical applications of Bayes' theorem also include a decay function, which treats newer data as more relevant or reliable than older data.

And while it is certainly true that in many realms — the sciences in particular — the impact of that decay function makes Chesterton's "democracy of the dead" infeasible, there are at least some realms — philosophy in particular — where we encounter what are arguably timeless truths, and the mere fact that Plato was the first to describe them, rather than a contemporary statesman, makes them no less true. Likewise, the mere fact that it was 2,500 years ago, rather than 25 years ago, when Pythagoras proposed his now-eponymous theorem about the sides of right triangles does not mean we should dismiss it as primitive or antiquated. Many of Chesterton's own writings have now passed the century mark, yet I am often struck by how prescient and relevant they remain.

Same old, same old?

Returning to Chesterton's Fence for a moment, my surprise that it is not met with universal acceptance in software engineering circles led me to consider the proposition with more scrutiny, and after learning more about Bayes' theorem, I had a bit of a breakthrough.

Chesterton approaches the problem of reform — in his case, he's focusing on religious reform — with some prior evidence that colors his thoughts on the matter. Specifically, he has seen self-appointed reformers attempt to dismantle institutions that he insists have important purposes, and in his view they have done so recklessly, without due consideration.

It is no wonder, then, that he recommends a cautious approach to reform; he is not opposed to reform in principle, as an arch-conservative might be, but he is opposed to rash reform based on the whims or fashions of the moment.

Yet I can envision a software engineer who has vastly different priors. Perhaps they have observed that in the vast majority of previous cases, when they have encountered code that, at first glance, serves no purpose, they have embarked on a quest to figure out why it was put there in the first place, only to find, after sufficient examination, that there was indeed no good purpose for it. If we give those prior experiences enough weight, they might lead us to reject the idea of Chesterton's Fence as foolish, impractical, or not worth the effort.

Tradition on trial

In our modern age, tradition often gets a bad rap. "We do it this way because that's the way we've always done it" seems like a flimsy justification for anything, much less important things.

It falls just one rung below convention, which is arbitrarily deciding to do something a certain way because there is some advantage to having only one way of doing it (such as the convention of driving on the right side of the road in the US).

Yet the tradition that Chesterton was defending was not the things we do for no other reason except that we've always done them. Rather, he was defending the things we do for a good reason we've forgotten — almost like an amnesiac who still wears a wedding ring even though they can't recall their spouse's name.

Chesterton touches on this in his book "Orthodoxy," in which he writes of his own foolishness in ignoring tradition:

If this book is a joke it is a joke against me. I am the man who with the utmost daring discovered what had been discovered before. If there is an element of farce in what follows, the farce is at my own expense; for this book explains how I fancied I was the first to set foot in Brighton and then found I was the last. It recounts my elephantine adventures in pursuit of the obvious. No one can think my case more ludicrous than I think it myself; no reader can accuse me here of trying to make a fool of him: I am the fool of this story, and no rebel shall hurl me from my throne. I freely confess all the idiotic ambitions of the end of the nineteenth century. I did, like all other solemn little boys, try to be in advance of the age. Like them I tried to be some ten minutes in advance of the truth. And I found that I was eighteen hundred years behind it. I did strain my voice with a painfully juvenile exaggeration in uttering my truths. And I was punished in the fittest and funniest way, for I have kept my truths: but I have discovered, not that they were not truths, but simply that they were not mine.

To put it another way, Chesterton, in his defense of tradition, urges us not to apply a time-decay function to the priors of our Bayesian inferences that might, to our detriment, underweight the value of timeless wisdom.

Does that mean that all traditions are above scrutiny? Certainly not. We can apply the principle of Chesterton's Fence to tradition, just as we can to any other institution seemingly in need of reform.

Recursive Bayesian reasoning

I hope this exploration of Chesterton's Fence, Bayesian statistics, and the value of tradition has been helpful to you in some way.

But perhaps you remain unconvinced and feel as if you need to test the application of these principles before you can fully buy in to them.

Well, Chesterton's Fence proposes a Bayesian approach to reform — but there's nothing stopping us from going meta and applying Bayes' theorem to Chesterton's Fence itself.

We might, for instance, assign a certain probability to the hypothesis that employing Chesterton's Fence leads to superior outcomes. And then, through multiple iterations, we can gather new evidence that helps us update that probability. It's a fitting application of the method, given that Chesterton's Fence itself is a call to fully understand our priors before making a decision.