This Online Experiment Identifies Dogmatic Thinking

You might be familiar with the words "dogma" or "dogmatic" in their religious sense: a set of beliefs that members of a religion are expected to accept as true.

But there is another, broader way that "dogmatic" is used that does not necessarily have to do with religious dogma.

In psychology, dogmatism is a defined as exhibiting great certainty about the correctness of one's views and an unwillingness to consider new evidence, or an unwillingness to adjust one's views in light of new evidence.

While it's certainly true that people can be dogmatic about their religious beliefs, that's not the only place where dogmatism surfaces. It's also possible to be dogmatic about political, scientific, or social issues.

One of the hallmarks of dogmatism is a lack of interest in, or hostility toward, any information that might challenge one's pre-existing views.

In a 2020 study, researchers from the University College London devised an experiment to help determine whether dogmatism occurs because people have strong opinions about specific subjects, or if there is a lower-level cognitive predisposition that leads to dogmatic thinking, even when people don't have strong pre-existing views.

Below, you'll have an opportunity to take part in an adapted version of the experiment they used in their study.

In this interactive, web-based version of the experiment, which takes about 5 minutes to complete, you'll play a fast-paced game, then answer some questions related to your beliefs about political and social issues.

After you complete the experiment, you'll learn whether your results are in line with the study's findings, and you'll also learn some practical takeaways we can derive from this research.

Ready to begin? Click one of the buttons below to continue.

That's the Spirit!

I'm glad you appreciate my sense of humor.

The Experiment

Below, you will play 10 rounds of a short guessing game. In each round, you can earn up to 100 points.

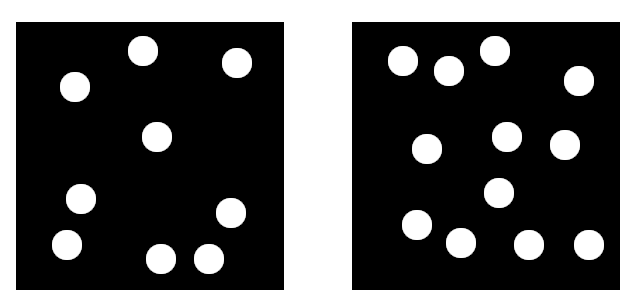

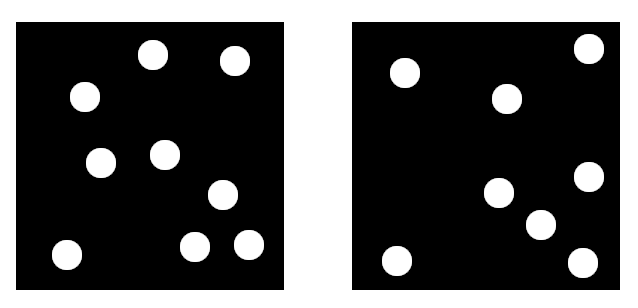

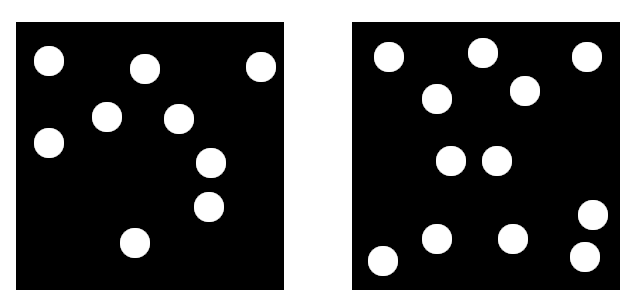

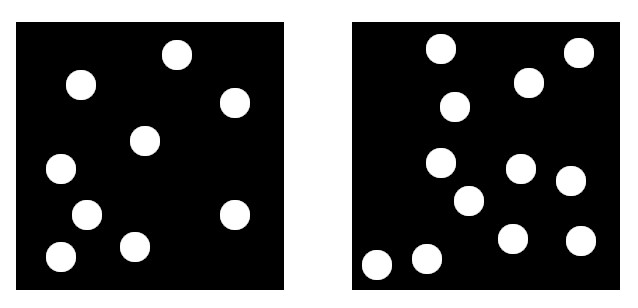

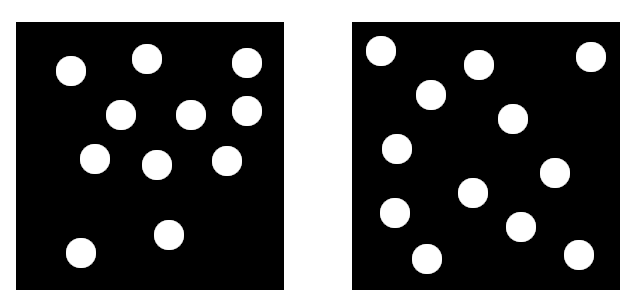

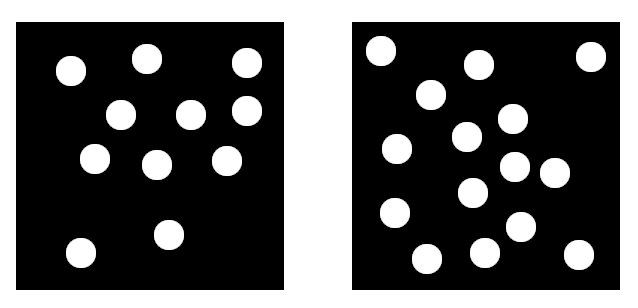

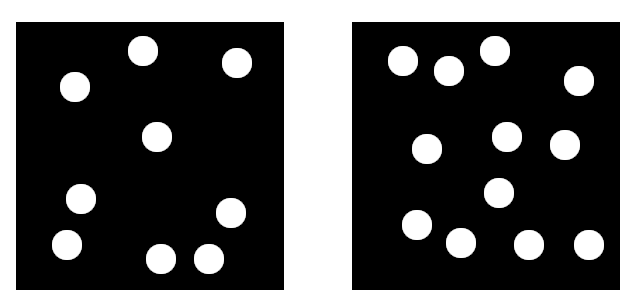

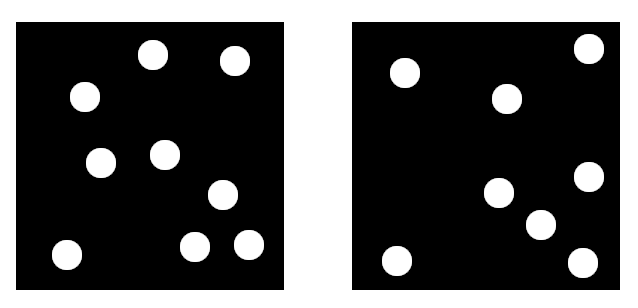

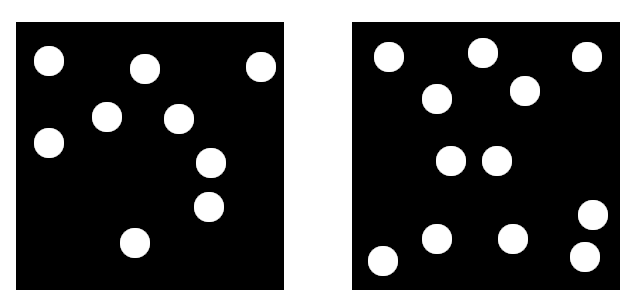

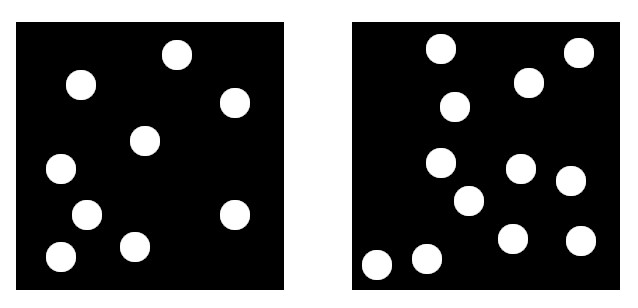

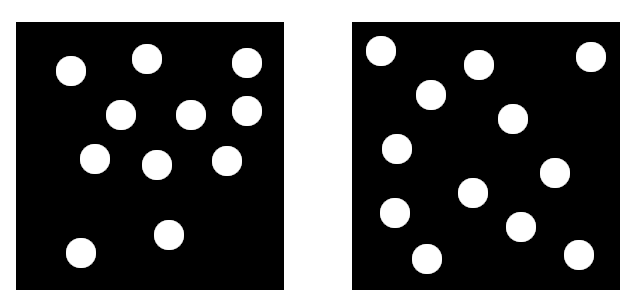

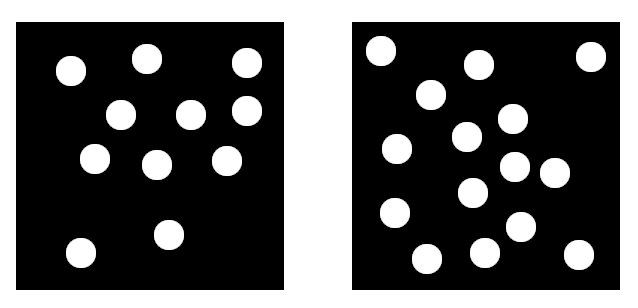

When a round begins, two black squares will briefly appear on the screen. One of the squares will contain more white dots than the other, and it's your job to decide which square has more dots.

After the black squares disappear, you'll be asked to make an initial guess and indicate how confident you are in your answer. This initial guess does not affect your score.

Then, you'll be given the opportunity to view an easier version of the task. But if you choose to view the easier version, it will cost you 20 points.

Afterward, regardless of whether you've chosen to view the easier version, you'll "lock in" your answer for the current round. If you've guessed correctly, you'll earn 100 points; if you've guessed incorrectly, you'll earn 0 points.

Try to earn the highest score you can. Once the game is over, you'll learn how you performed compared with other players.

Initial guess

Which square contained more dots? Your response here indicates your initial answer, but you'll have an opportunity to revise this answer.

(High certainty)

(Medium certainty)

(Low certainty)

(Low certainty)

(Medium certainty)

(High certainty)

You can view an easier version of this round, but it will cost you 20 points.

Final answer

Which square contained more dots? You'll earn 100 points for a correct response and 0 points for an incorrect response.

(High certainty)

(Medium certainty)

(Low certainty)

(Low certainty)

(Medium certainty)

(High certainty)

Survey question 1 of 10

Our government has a duty to provide health care to citizens.

Survey question 2 of 10

Those whose opinions about government-provided healthcare differ from mine have been misled.

Survey question 3 of 10

The consequences for entering our country illegally should be more severe than they are now.

Survey question 4 of 10

Those whose opinions about illegal immigration differ from mine are either foolish or immoral.

Survey question 5 of 10

If our country's traditions upset some people, those traditions should be denounced and discarded without hestitation.

Survey question 6 of 10

My opinion about our country's traditions is the only reasonable one. People who disagree are welcome to move somewhere else.

Survey question 7 of 10

I may be wrong about some of the little things in life, but I am sure I am right about the most important things.

Survey question 8 of 10

Being open-minded is only beneficial if your original beliefs are wrong.

Survey question 9 of 10

I find it irritating when people question every rule they encounter.

Survey question 10 of 10

"The object of opening the mind, as of opening the mouth, is to shut it again on something solid." — G.K. Chesterton

See below for your results!

The Results

Your score on the "Which box has more dots?" game is .

Out of the people who have participated in this experiment so far, the average score on the "Which box has more dots?" game has been . (The highest possible score is 1000 points.)

The average participant opted to view the easier version of each round times out of 10, and they guessed correctly times out of 10. Because the price to view the easier version is 20 points each round, a participant could opt to view the easier version in all 10 rounds and (assuming the extra information helps them choose the correct answer each time) still end up with a score of 800 points. Thus, the most reasonable strategy is to view the easier version in any round where you experience anything other than high certainty about the correct answer during the initial judgment.

The survey questions, which are intended to measure your level of dogmatic thinking, are used to determine your dogmatism score, on a scale from 1 (least dogmatic) to 5 (most dogmatic). Your political positions about health care, immigration, and national traditions are not factored into this score, but your opinions about those who disagree with you do affect your score. Your score of is the average score of . Among participants in the highest quartile, the average score is ; among participants in the lowest quartile, the average score is .

The fact that your dogmatism score is lower than average, while your game score is higher than average, is consistent with the idea that dogmatism is associated with lower likelihood to engage in information search.

The fact that your dogmatism score is higher than average, while your game score is lower than average, is consistent with the idea that dogmatism is associated with lower likelihood to engage in information search.

The Research

How much time do you invest before making up your mind about something?

Gathering evidence from trustworthy sources to help shape your opinion can be a difficult and time-consuming task, and few people have the free time or interest to turn this search for evidence into an all-consuming, open-ended quest.

Thus, rather than reserving judgment until we've exhaustively researched a topic, most of us will form an initial opinion based on whatever evidence is readily available.

But what happens if we later encounter evidence that supports an opposing point of view?

A perfectly rational response is to update our previously held views to account for this new evidence.

However, numerous studies have shown that people tend to trust evidence that confirms their existing views and discount or dismiss evidence that conflicts with those views.

A person with intense views about economic policy might, for instance, read about a study that supports their views, and they might take it as strong confirmation that their views are correct. But they might read about a separate study with evidence against their views, and they are more likely to dismiss it. They might accuse the researchers of bias or incompetence, or come up with some other reason why the evidence is untrustworthy or should not lead them to abandon their existing views.

Going one step further, people who exhibit a personality trait known as dogmatism not only dismiss evidence that conflicts with their existing views but also exhibit higher certainty about their opinions than is warranted and show little interest in exploring additional evidence. Close-mindedness and a lack of intellectual humility are hallmarks of dogmatism. People who exhibit this trait are often described as set in their ways, unwilling to seriously entertain opposing views. They are also very likely to prefer an echo chamber of ideas, where they only consume sources of information that reinforce their existing views and avoid sources of information that might call those views into question.

In a 2020 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers from the University College London attempted to determine whether dogmatism, as a personality trait, is motivated by strong existing beliefs about religious, political, social, and scientific subjects — or whether it might be detectable even in cases where strong prior beliefs are not present.

They devised an experiment, similar to the one presented here, where participants had to make judgments in the face of uncertainty. The participants were briefly shown two images of black boxes, each of which contained some number of white dots, and they had to judge which box contained the most dots.

In each round, participants were given the option to view an easier version of the task, where the difference in the number of dots was more pronounced. There was a small penalty associated with viewing the easier version, but the penalty for getting the wrong answer was much larger, so if a person was unsure about the correct answer, it was generally advantageous to view the easier version.

The participants also filled out a questionnaire to gauge their level of dogmatism. The questions covered political and social issues and also touched on how certain they were that their opinions were correct, how open-minded they were, and how rigid their beliefs were.

The researchers found that there was a link between a person's level of dogmatism, as measured by the questionnaire, and their willingness to seek out information in the face of uncertainty, as measured by how often they chose to view the easier version of the "Which box has more dots?" game.

The higher a person scored on the dogmatism scale, the less likely they were to seek out extra information by viewing the easier version in each round.

Could it be that these dogmatic thinkers just happened to be better at the game than the average person, so they had less need to view the easier version?

No, the researchers found that their performance at the task suffered because of their unwillingness to view the easier version when they were uncertain about the correct choice.

This study's findings lend weight to the idea that dogmatism doesn't occur purely because some people have strong prior beliefs or expectations that they are unwilling to discard in the face of disconfirming evidence. The study's participants could not have had any strong prior beliefs about which box contained more dots — yet they still were reluctant to view the easier version of the problem.

This suggests that dogmatic thinkers aren't necessarily driven by ideological blind spots on specific issues about which they have preconceived notions. Rather, they exhibit a general unwillingness to seek out or examine new evidence that has the potential to increase the accuracy of their judgments.

The Takeaway

The results of this study reveal new insights about what contributes to dogmatic thinking.

They also suggest that dogmatism is a personality trait that is likely to affect many facets of a person's life, rather than being limited to a certain subset of strong beliefs about individual issues. A person who exhibits dogmatic thinking in one area of their life probably exhibits the same pattern in other areas.

So if someone in your life fits the mold of a dogmatic thinker — dismissive of opposing viewpoints and evidence — what can you do to help them be more open-minded?

The short answer: There may not be much you can do to fundamentally change this aspect of their personality, at least not through any short-term intervention.

Just as paranoia can be hard to treat because it often involves unreasonable beliefs about whether the treatment is intended to help or harm, dogmatism can be hard to address because dogmatic thinkers often hold unreasonable views about the likelihood that their beliefs are incorrect. In both the case of paranoia and dogmatism, the individual isn't at all likely to be convinced that the problem is with them, rather than with other people.

But understanding the "why" behind these behaviors can help you better assess whether dialog with a dogmatic thinker is going to be productive.

If you know that they will delegitimize evidence that conflicts with their pre-existing beliefs, no matter how compelling it is, then while you might not be able to sway their opinion, at least you can avoid a fruitless conversation.

There is one other takeaway worth considering.

Although close-mindedness tends to be considered a negative personality trait in the abstract, might there be some cases where close-mindedness is beneficial?

Heather Battaly, a philosophy professor at the University of Connecticut, argues in a 2018 paper published in the journal Episteme that close-mindedness is not always an intellectual vice — that is, a way of thinking that leads to unreasonable conclusions or inaccurate judgments. In fact, in some cases, it can be a virtue.

Battaly draws the distinction between ordinary environments, where most people seem to be seeking the truth in good faith, and "epistemically hostile" environments, where suppression of the truth is pervasive, a la George Orwell's "1984," or where most people are too foolish to discern the truth, a la Mike Judge's "Idiocracy."

In ordinary environments, it's not necessarily close-minded to ignore fringe theories that require one to call into question a preponderance of evidence to the contrary, such as with the assertions "2 + 2 = 5" or "The moon landing was faked."

In epistemically hostile environments, however, the pervasiveness of evidence in favor of a particular point of view does not necessarily indicate that the evidence is reliable. However much Orwell's Ministry of Truth insists that "Ignorance is Strength," a truth-seeking person in that environment would do well to remain close-minded against the ideas expressed by the ministry's propaganda.

About Shaun

Shaun Gallagher is the author of three popular science books and one silly statistics book:

He's also a software engineering manager and lives in northern Delaware with his wife and children.

Visit his portfolio site for more about his books and his programming projects.

The views expressed on this blog are his own and do not necessarily represent the views of his publishers or employer.

Recent posts

This online experiment identifies dogmatic thinking

Adapted from a 2020 study, this web experiment tests a cognitive quirk that contributes to dogmatic worldviews.

Distributism: A Kids' Guide to a Third-Way Economic System

This student guide explores three economic systems (capitalism, socialism, and distributism) and explains how distributism is different from the other two.

You can thrive in a high-paying career without being money-driven

What if making money is not one of your top goals? And what if you happen to stumble into a high-paying career nonetheless?

On compassionate code review

How to build up and encourage code authors during the review process

Rules for Poems

A poem about all the rules you can break — and the one rule you can't.