Distributism:

A Kids' Guide to a

Third-Way Economic System

Note: Although this guide is written for upper elementary and middle school students, it's suitable for any reader who is new to distributism or economics in general. For students, teachers may consider using it as a supplementary resource within their social studies curriculum or an extra-credit reading assignment.

Within a society, the ways that businesses are owned and operated can vary. Some businesses can be owned by a single person. Others can be owned by hundreds of thousands of people. Still others can be owned and run by the government, rather than private citizens.

In this guide, you are going to learn about three different ways of thinking about business ownership. Two are well known, and another is lesser known but has some important benefits over the other two.

Before diving in to those three approaches, let's answer some basic questions: What is an economy, and what is productive property?

What is an economy?

The word economy has several meanings, but its normal meaning refers to how things are bought and sold within a society, and how people make their living. Generally, when we talk about "the economy" or "economic activity," we are talking about the way businesses operate, the way people earn money, and the way the government makes rules about trade (selling or buying by businesses or people).

In a healthy economy, businesses sell things that shoppers want to buy, and shoppers have enough money to buy those things because they're earning enough money from their jobs.

The economy is often regulated by the government, which makes laws about what businesses can and can't do. For instance, there might be laws that are intended to ensure the safety of workers and customers, as well as laws against trying to damage or shut down competing businesses using unfair tactics. The government can also influence the economy in other ways, such as by regulating its currency or by making it more or less expensive for businesses and people to borrow money. And, of course, the government can also raise and lower the taxes it requires businesses and people to pay.

What is productive property?

Normally, the way a person makes a living is by combining two things — property and labor — to produce something of value that somebody else wants to buy.

For instance: A baker owns a bakery and baking equipment. She buys ingredients and uses her own labor to make cakes, which she then sells. A portion of the money she makes from cake sales goes to expenses related to operating the business (mortgage, upkeep of the building and equipment, cost of ingredients). The rest of the money is considered profit, and the baker gets to keep it, because she owns the business.

We call the bakery and equipment "productive property," because they are used to produce the cakes that are for sale. For a farmer, his land and farming equipment are productive property. For a taxi driver, his vehicle is productive property. In the case of a doctor, productive property might include the medical equipment she uses and the office where she sees patients.

What are socialism and capitalism?

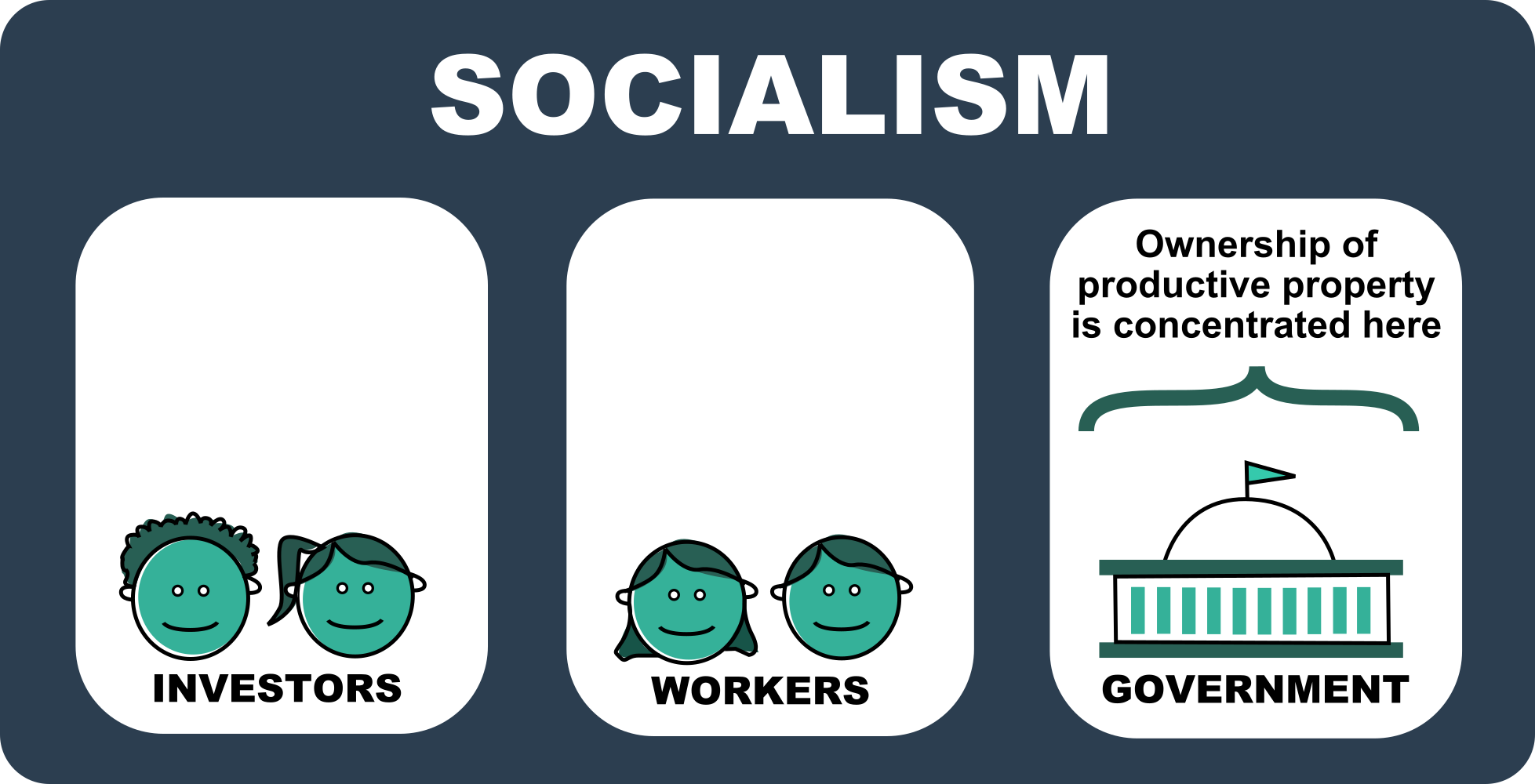

In an economic system called socialism, the government owns most productive property.

Government-owned businesses employ workers, who supply the labor to produce the goods and services that the businesses sell.

When these businesses make money, the government gets to decide what to do with that money, because it owns the business. The workers may earn wages for their labor, but because they don't own the business, they don't have ultimate control over how it operates or how profits are dispensed.

If the government leaders are corrupt or power-hungry, they might make bad decisions that enrich themselves at the expense of the workers.

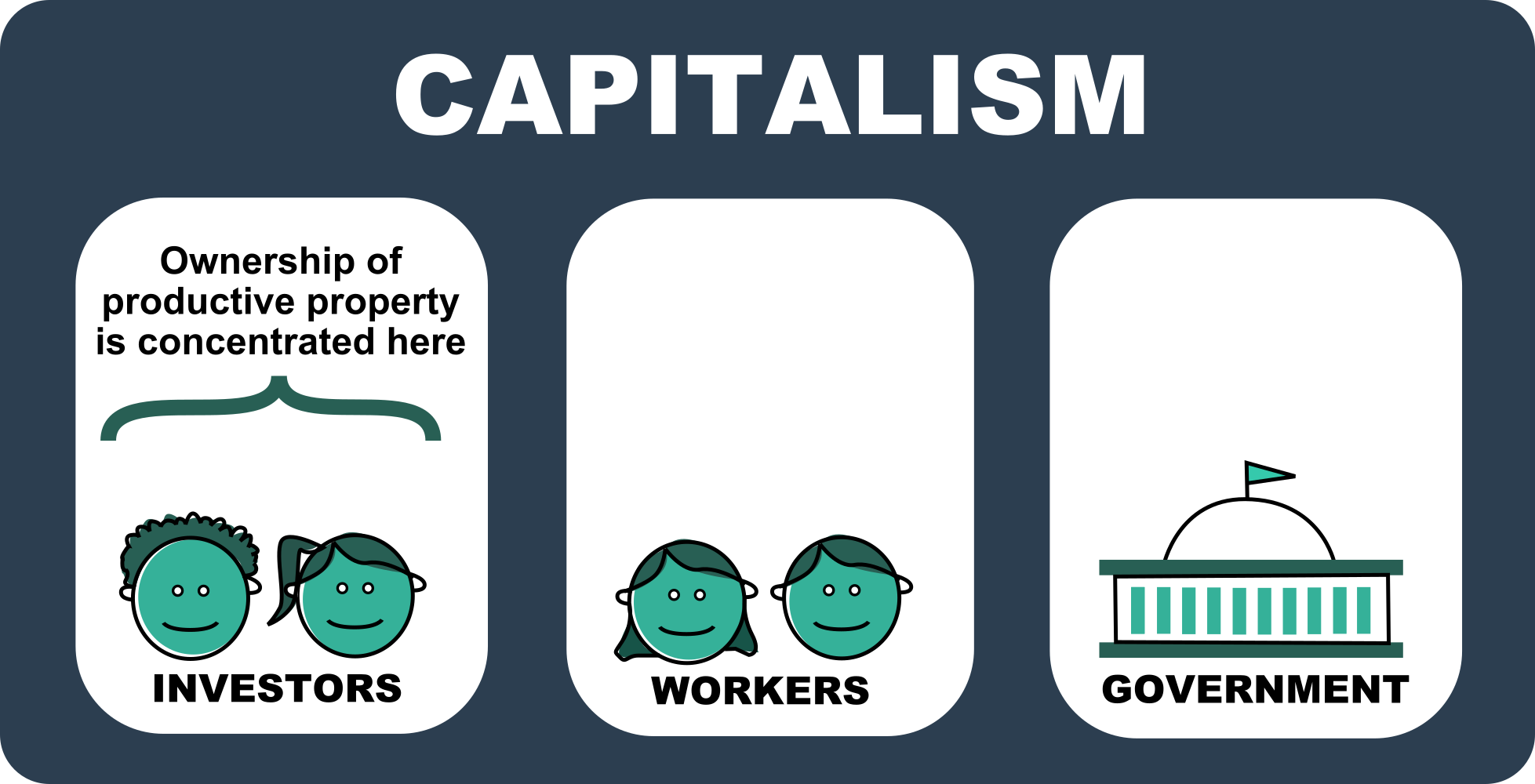

In an economic system called capitalism, productive property is owned privately, not by the government.

Often, when someone is starting a business, they don't have the money to buy all the productive property they need to get it up and running, so they accept money (called capital) from outside investors, and in exchange the investors become part owners of the business.

Those investors receive a portion of whatever profits the business makes, and they also usually get a say in how the business is operated. One thing they don't usually do is supply labor.

Instead, the business hires employees. These employees are paid wages, but they don't typically share in the ownership of the business, which means they don't share in the profits or have an ultimate say in how the business is operated.

What's the problem?

The main problem with both of these economic systems, socialism and capitalism, is that ownership of productive property ends up becoming concentrated in the hands of a small number of people.

Under socialism, a small number of government leaders control the government-owned businesses and productive property, and they get to make the decisions. If they make bad decisions, the money generated by the workers' labor gets put to bad use.

Under capitalism, a relatively small number of wealthy investors own most of the productive property, and over time, that wealth and ownership becomes even more concentrated. As that happens, it becomes harder for people to own businesses that can compete against the big guys. Thus, the vast majority of workers end up as employees who don't own the businesses they work for. Instead, the profits generated by their labor serve to further enrich the wealthy investors.

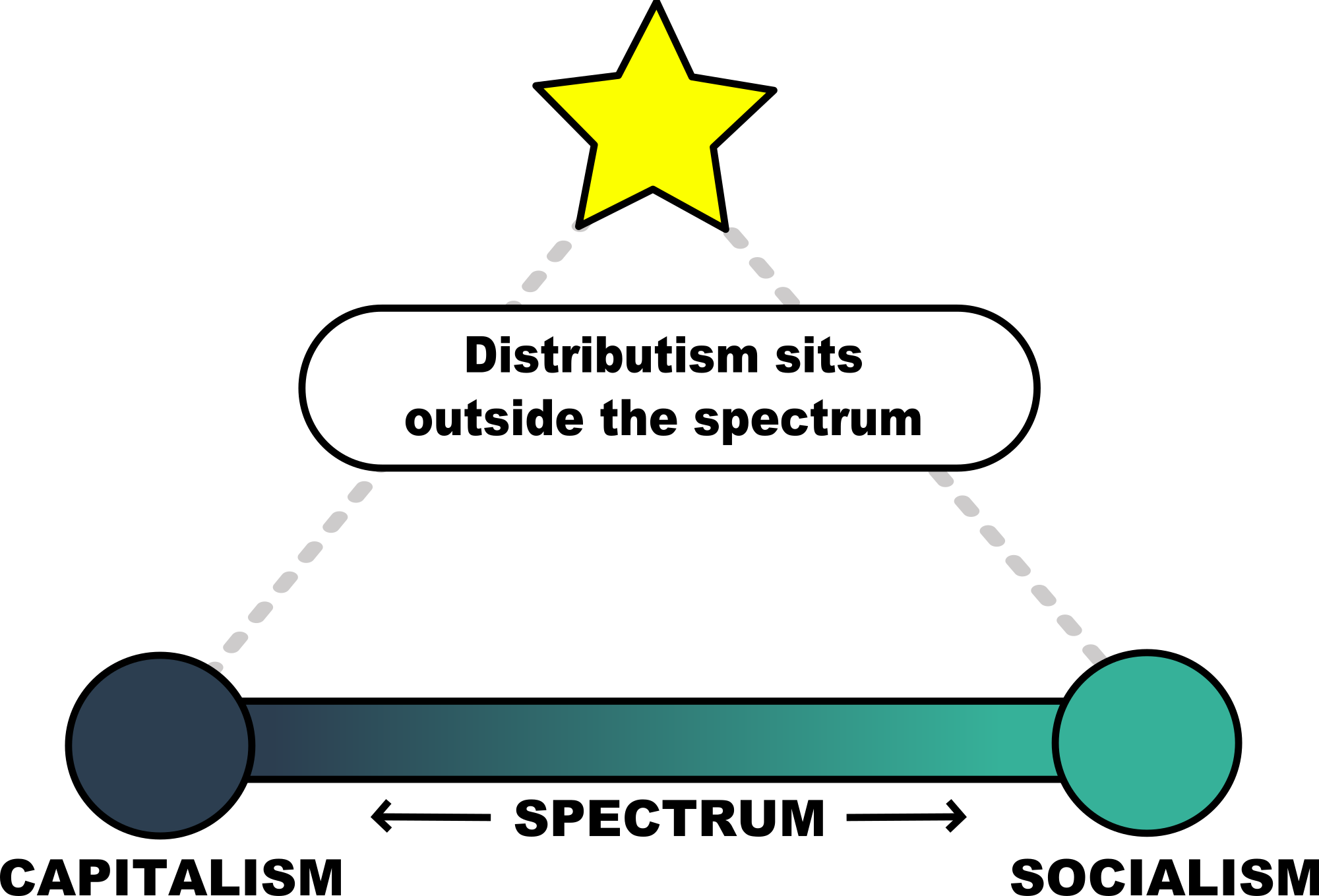

Many people think capitalism and socialism are the only two ways an economy can operate, or they see capitalism and socialism as two extremes on a spectrum, where some economies are mostly capitalist with a bit of socialism or mostly socialist with a bit of capitalism.

For instance, many countries throughout the world attempt to combine capitalism and socialism by permitting private ownership of productive property, but with high enough tax rates that the government is able to provide and run a wide variety of social services, such as health care, welfare programs that help the poor, and pension programs that help the elderly and retired.

In fact, relatively few countries go all-in with either capitalism or socialism.

But even with a blended model — one that incorporates a bit of both capitalism and socialism — we still see that the ownership of productive property tends to become more concentrated over time.

What is distributism?

Fortunately, capitalism and socialism are not the only possible types of economies, nor is the capitalist-socialist spectrum an accurate way to think about the possibilities.

There is a third-way economic system called distributism that is different from both capitalism and socialism. It's not a "middle ground" approach that sits somewhere along the spectrum between the two. Instead, it sits outside the spectrum, sort of like how the third point on a triangle does not rest anywhere on the line that connects the other two points.

Distributism seeks to avoid the problem that occurs in both socialism and capitalism: ownership of productive property becomes concentrated in the hands of a small number of people.

The guiding principle of distributism is that ownership of productive property should be as widespread as possible.

In a distributist economy, most workers have an ownership stake in the businesses they work for, and when the business succeeds, they benefit from that success as well.

Distributism also advocates for changes to government regulations that put small businesses at a disadvantage over larger businesses. For instance, within a capitalist model, it can be difficult for a small business to compete against a larger business, even if the small business is able to provide superior products or services.

When large corporations use their size to drive smaller competitors out of business, it has a negative impact on the small-business owners, and it also has a negative impact on consumers, who now have fewer choices about where to shop.

In fact, over time, the problem tends to grow worse. As large corporations grow bigger, they can more easily drive away smaller competitors. With fewer competitors, the corporations grow bigger still. Meanwhile, people who might otherwise become small-business owners instead can only find stable work by becoming employees of large businesses.

Economists have noticed this happen, and they've even given it a name: "The Wal-Mart Effect." When a large corporation such as Wal-Mart opens in a new area, smaller existing businesses are often disrupted, and wages go down. Then, because wages have dropped, more people become reliant on government aid to meet their basic needs, a cost that is ultimately born by taxpayers.

But when government policies allow small businesses to flourish, they become less susceptible to these effects.

And when a large percentage of people are owners, rather than just wage earners, it benefits society in many ways. For instance:

• Wealth inequality (the difference between the richest and poorest people in society) goes down.

• Worker exploitation goes down.

• Businesses succeed because they're well-run and provide valuable goods and services, not just because they're big enough to shove everybody else out of the way.

Does anyone's property get taken away?

"Distributism" can be a confusing name. You might think that it means money and property should be forcibly taken from the rich and distributed to the poor, sort of like how Robin Hood operates. But that is not what distributism advocates.

Rather, distributists advocate for economic policies that make it easier for people to own productive property, individually and together, and use that property to make a living.

For instance, distributists advocate for policies that prevent big businesses from unfairly muscling out small businesses, such as laws against anti-competitive business practices. Distributists also advocate for changes to economic policies that give wealthy investors unfair advantages over workers, such as lower taxes on income from investments than on income from labor.

What are cooperatives?

One of the biggest practical examples of distributism in action is a business structure known as a cooperative.

$

$

$

Business receives income

Employees get paid wages

Owners (often investors)

$

$

$

Business receives income

Employees get paid wages

Owners (often investors)get the rest

A cooperative is a business that is 100% owned by its members, with no outside investors. For instance, a group of farmers or a group of website designers might form a worker's cooperative, which allows them to operate more efficiently than if they were all working separately. Every member of the co-op has an ownership stake, which means every member gets a say in how the business is operated, and they also get a share in the business's profits. Another example is a grocery store organized as a consumer cooperative. In this case, it's the people who shop there who are the member-owners, and they get to vote on how the store operates and share in the store's profits, usually in the form of rebates based on how much they purchased.

There are many examples of successful cooperatives throughout the world:

$

$

$

Business receives income

All profit goes

$

$

$

Business receives income

All profit goesto worker-owners

• In Europe, large cooperatives such as Spain's Mondragon (a worker co-op) and England's The Cooperative Group (a consumer co-op) are well known.

• In the United States, all credit unions and mutual insurance companies are incorporated as cooperatives.

• There are also several well-known U.S. consumer brands and stores, such as Shoprite, Land O'Lakes, ACE Hardware, and and REI, that are organized as co-ops.

Just as with traditional investor-owned businesses, cooperatives can come in many sizes. Not everyone is cut out to be a small-business owner, but just about anyone who could be employed by an investor-owned business could also work for a comparable cooperative.

Who came up with distributism?

Distributism began taking shape in the late 1800s and early 1900s as a way of applying Catholic social teachings to economic issues. Among the influential early proponents of distributism were Catholic authors G. K. Chesterton and Hilaire Belloc.

Although distributism was inspired by Catholic teachings around social justice and worker's rights, distributism isn't an inherently religious concept. Rather, it's a set of ideas that recognizes some of the perils of capitalism and socialism and proposes economic principles that promote a free and just society -- one that puts the good of the people first, rather than being primarily influenced by the interests of Big Business or Big Government.

Can I be a distributist?

Distributism has a historic connection with Catholicism, but you don't need to be Catholic, or Christian, or believe in God, to be a proponent of distributism.

To put it another way, you can recognize the benefits of distributism regardless of your religious views.

So if the idea of distributism appeals to you, yes, you can be a distributist!

What can I do?

• Although you might have a bank account, your parents or guardians probably make the decisions about where to bank. If they are not already a member of a credit union (a type of cooperative), encourage them to join one and establish an account for you.

• Support small businesses in your area, and try to buy locally produced goods and services. Money spent at locally owned businesses tends to circulate within your local economy to a greater degree than money spent at chain stores.

• Are there any worker-rights movements in your area? Consider attending an event or demonstration.

• One of the biggest things you can do as a distributist is educate others about the benefits of distributism. But keep in mind, this guide is only a start. If you're really interested in business and economics, visit your local library and look for books on the subjects. If your library uses the Dewey Decimal System, many of these books can be found in the 330-339 section of the nonfiction collection.